Image from: Animals Australia: Australia’s Secret Primate Experiments

Animal experimentation has always been vital to our survival and scientific advancement. During the Renaissance, trapping mice in vacuum seals led to the discovery of oxygen being the key to our survival, allowing doctors to better understand organ systems (Physiology In the Renaissance Period – Dr. Duffin). The rise of Positivism saw beliefs moving away from theology, toward real observations. Francois Magendie conducted experiments that involved removing animals’ organs and keeping them alive to see how their bodies adapted (Physiology In the Pre-Modern Period – Dr. Duffin). This progressed the field of physiology, and helped in the discovery of different disease treatments.

Image from: Animals in Biomedical Research: What They have Given Us and What We Owe Them

Animal experiments since, have saved lives around the world. For the anti-emetic Thalidomide, it was only after being tested on pregnant animals and observing babies born with severe deformities that the FDA banned its sale across America, saving many babies from lifetimes of suffering (Animals in Biomedical Research). This shows the unequivocal importance of animal experimentation to human life.

Past ethical failures like the Tuskegee experiments saw disadvantaged Black populations lied to about receiving Syphilis treatment. Public health services justified it as a “study in nature [of the disease]” and purposefully let hundreds of people die (McGill: 40 Years of Human Experimentation in America: The Tuskegee Study). Such events, along with eugenics-based genocide in Nazi Germany sparked the creation of strict regulations, such as the Helsinki Declaration, for human and animal welfare in modern clinical trials (Animals in Biomedical Research). Animal experimentation not only saves human lives, but we actively uphold animal welfare standards.

My opinion on this topic however, is that animal experimentation is generally wrong. I decided to talk to my friend about this issue, and here’s what she had to say:

I believe that animals have moral worth independent of their usefulness to humans, and that their basic interests should have similar consideration to ours (PETA – Why Animal Rights). This concept leads me to the three Rs of animal experimentation used today. They describe the need to reduce animal involvement, replace them when possible with other methods, and minimize their suffering (Animal Use Alternatives 3Rs). This proves that within the scientific community, people already acknowledge that animals are worthy of moral consideration. A researcher at a UK university said “I’d spend entire [days] just breaking necks…and being part of their suffering left me feeling like there wasn’t much point in my existence” (VICE news). Researchers suffering perpetrator-induced trauma gives me a glimpse into how violent experiments truly are which only strengthens my opinion against animal experimentation.

In my opinion, animals are fundamentally people. If we consider a person to be someone who can feel emotions, sensations and have complex thought, animals would have personhood, thus affording them more legal protection (TEDx Cambridge: Are There Non-Human Persons). But they don’t. Why? Peter Singer, a famous philosopher, said “if possessing a higher degree of intelligence [doesn’t] entitle one human to use another for his own ends, how can it entitle humans to exploit non-humans?” (Britannica – Peter Singer). The speciesism prejudice humans show in treating other humans better than non-human animals, is no different than one type of human being owned and exploited by another, on the basis of race. I mean, how would you feel if your freedom was stolen?

Image from: Our Compass: The High Cost of Animal Testing

Image from: Cavendish Historical Society News

Alexis St. Martin was a Canadian indentured servant who was experimented on by physician William Beaumont (Alexis St. Martin: A Hole In the Stomach). Dr. Beaumont healed his abdominal gunshot wound, saving his life. Afterwards, he often forcefully experimenting on the fistula it left, making Alexis suffer. Alexis claimed many times that he didn’t want to live like a guinea pig, and that he owed Dr. Beaumont something but not his whole life (Physiology in the Pre-Modern Period – Dr. Duffin). When researchers provide animals with “sanitary environments” or other basic needs as a sort of justification to experiment on them, how is that any more ethical than Dr. Beaumont saving Alexis’s life yet forcing him to endure what he had to?

Image from: Animal Research at Queen’s

When I went vegan, my shift in perspective scrutinized not just my dietary choices but how I supported industries that harmed animals. However, the only instance in which I do “support” animal experimentation is when it’s vital to our survival (American Psychological Association). Getting vaccinated, or taking certain medicines saves millions of lives, and the animals’ sacrifices are taken for granted. This is why I realize that my stance still causes immense suffering, and there are many limitations to it. How do researchers decide which types of medicine are worthy to be tested on animals, or how to quantify harms vs benefits?

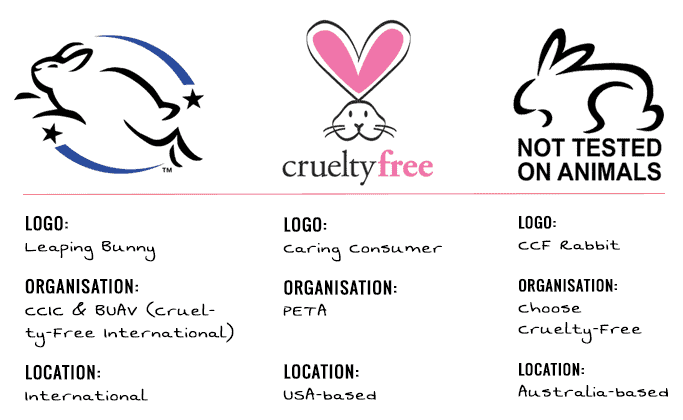

Image from: Cruelty-Free Kitty: How to Spot a Fake Cruelty-Free Logo

In my daily life, I do my best in making mindful choices such as always buying cruelty-free personal products thus denying money to companies perpetuating unnecessary violence. As experimentation methods advance, animals’ roles in medicine will slowly be omitted. Until a “liberation” day arrives, I believe everyone must make ethical decisions, yet value human life.