From diabetes to arthritis, we all want to cure our health issues. But does our desperation give pharmaceutical companies the right to advertise directly to us? Let’s explore DTCA (direct-to-consumer advertising), and all its’ shades of grey.

DTCA is the practice of pharmaceutical companies advertising their products directly to their target population, through the internet television, or other media (Health Charities Coalition of Canada). Canada’s FDA prohibits DTCA by preventing the promotion of any drug as a cure, treatment or prevention to serious diseases like cancer, diabetes, etc. (DTCA in Canada – NIH). Despite government regulation, at the end of the day shouldn’t it be every business’s right to advertise their product? Not exactly. Over 20% of new Canadian drugs receive ‘black-box’ warning (having caused severe side-effects/death) after airing ads, highlighting the importance of DTCA regulations (DTC prescription Advertisements in Canada). The back and forth of companies wanting to advertise, while considering the seriousness of the product is primarily why this such a controversial social issue.

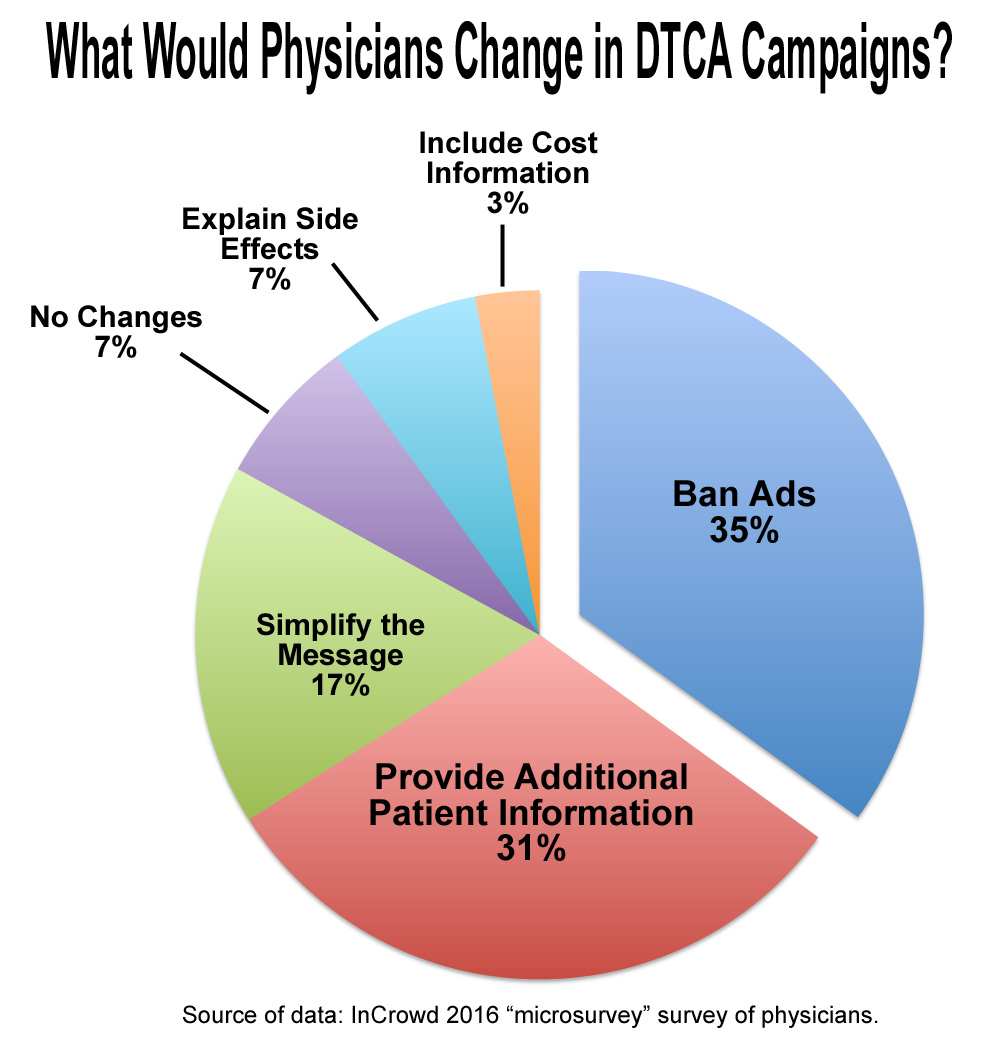

Deciding whether DTCA should be allowed or not, requires considering both sides of the argument. One reason against DTCA is over-prescription. Three Canadian studies between 2000-2002 found that 48% of physicians didn’t agree with DTCA drug referrals, yet still prescribed them for the patient’s peace of mind (DTC advertising and prescribing), demonstrating serious impact on patient care and prescription patterns (DTC advertising and prescribing). This over-prescription directly impacts healthcare costs. Because so many government-led programs pay for brand-name prescription drugs, vastly more expensive than generic counterparts, these schemes utilize increasingly higher amounts of tax dollars (Dangers and Opportunities of DTC Advertising). Less money goes into resolving bigger health determinants like SES/food deserts, which more immensely impact health.

Another major issue is misinformation. When ads list dangerous side-effects like the visuals try to illicit classical conditioning (Public Health Effects of DTC Drug Advertising). Someone happily playing with their dog gets associated with the drug, demonstrating the manipulative tactics used to lure people into becoming ill-informed customers. A study from the US found that amongst 97 advertisements, 0% provided adequate information regarding risks, and over 13% promoted an off-label use, which isn’t allowed as per FDA rules (Dangers and Opportunities of DTCA) demonstrating the manipulation DTCA uses to draw attention away from risks, towards the over-exaggerated benefits. While perhaps beneficial in some ways, DTCA manipulates vulnerability for profit.

While reasons against DTCA are valid, many reasons support it as well. When drug dispensaries first became publicly available, it revolutionized healthcare by giving people the opportunity to take charge of their own health, which is something I believe we take for granted today (The Emergence of the Drug Dispensary – Module 5). DTCAs are also excellent at informing the public about their treatment options. A study in 2004 found that 73% of physicians believed that DTCA helped their patients ask more thoughtful questions (DTC Pharmaceutical Advertising – NIH). This encourages conversations between patients and physicians thus improving disease awareness and health outcomes (Direct-to-Consumer Advertising and the Patient–Prescriber Encounter – NIH). In today’s 15-minute appointment world, people taking initiative for their health and reaching out to doctors allows for better health literacy/discourse, and quicker treatment (Understanding Health Literacy – CDC).

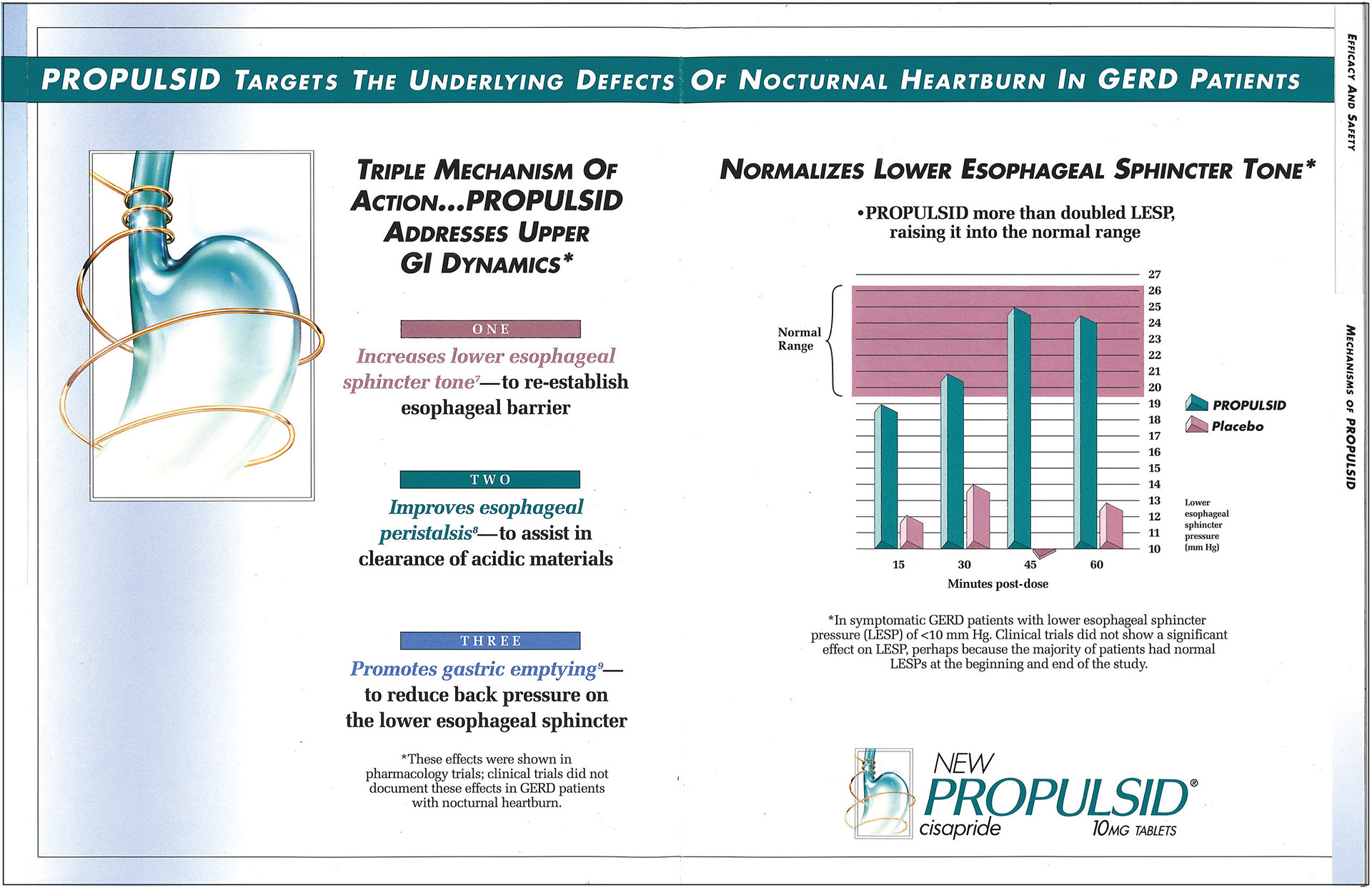

Organization like the FDA claim to “maintain comprehensive surveillance of medications to both consumers and physicians”, however many examples show it’s not enough. Propulsid was a gastric reflux drug heavily marketed to US consumers for 7 years before it was “black-boxed” due to high incidences of fatal heart arrythmias (DTC Pharmaceutical Advertising). Janssen the parent company, marketed Propulsid as a magic bullet; a drug only affecting the disease/issue and harming nothing else in the body (Magic Bullet Treatments – Dr. Duffin). Just looking at the advertisement, manufacturers used misleading graphs to lure consumers, while in fine print stating that it actually showed no effect in clinical trials. This demonstrates a clear example of DTCA being fatally misleading, and why it’s wrong.

Overall, I oppose DTCA. DTCAs sometimes use ghost-written studies where clinician academics ”co-investigate” heavily biased studies, but publish results as “properly conducted” (Ghost Management and Ghost Writing – Module 5) causing disease mongering by creating a demand for an issue that isn’t really there (Disease Mongering – Module 5). This leads to many drugs being ‘black-boxed’ with parent companies under-advertising risk and over-advertising benefits; why YOU need THIS drug NOW. Perhaps combatting DTCA misinformation requires imposing stricter regulations and gaining a better understanding of our healthcare system and our doctors’ choices. Decreasing prescription dependence, and increasing herbal medicine consumption can also help (Plant-Based Treatments – Dr. Duffin). Normally for a cold, instead of taking pills I drink “haldi doodh”, an ayurvedic plant-based drink that combats inflammation, to feel better.

I acknowledge that all DTCA pharmaceuticals aren’t inherently “evil”; and ultimately it’s up to the consumer to “talk to their doctor and see if ___ is right for them”. However, DTCA poses risks like over-prescription, and manipulative/misinformed advertising which harm patient care, and strain healthcare systems. This is why I believe it shouldn’t be allowed.